4 Educational Philosophies

Ken MacMillan, 3M National Teaching Fellow, and the 2015 recipient of the UCalgary Award for Educational Leadership) has shared an example educational leadership philosophy statement here. Table 1: Key components of a teaching philosophy statement with guiding questions for reflection. Some of the most prominent philosophies on education are the Montessori method, the Dewey method, the Holt method, and the. Some people think that Behaviorism, Cognitivism, Humanism, and Constructivism are philosophies of education that focus on who to teach and how to teach. May 21, 2014 at 7:59 AM Post a Comment.

Child centered education 2. Education as the natural development of the child’s power and capacities 3. Negative education in early childhood 4. Education should be based on child's psychology 5. The role of teacher should be that of a guide 9. Learning by doing 2.Play way method 3. Observation and experimentation 4.

Related Theories of Learning (Psychological Orientations)

Related to both the metaphysical worldview philosophies and the educational philosophies are theories of learning that focus on how learning occurs, the psychological orientations. They provide structures for the instructional aspects of teaching, suggesting methods that are related to their perspective on learning. These theoretical beliefs about learning are also at the epistemic level of philosophy, as they are concerned with the nature of learning. Each psychological orientation is most directly related to a particular educational philosophy, but may have other influences as well. The first two theoretical approaches can be thought of as transmissive, in that information is given to learners. The second two approaches are constructivist, in that the learner has to make meaning from experiences in the world.

Information Processing

Information Processing theorists focus on the mind and how it works to explain how learning occurs. The focus is on the processing of a relatively fixed body of knowledge and how it is attended to, received in the mind, processed, stored, and retrieved from memory. This model is derived from analogies between how the brain works and computer processing. Information processing theorists focus on the individual rather than the social aspects of thinking and learning. The mind is a symbolic processor that stores information in schemas or hierarchically arranged structures.

Knowledge may be general, applicable to many situations; for example, knowing how to type or spell. Other knowledge is domain specific, applicable to a specific subject or task, such as vowel sounds in Spanish. Knowledge is also declarative (content, or knowing that; for example, schools have students, teachers, and administrators), procedural (knowing how to do things—the steps or strategies; for example, to multiply mixed number, change both sides to improper fractions, then multiply numerators and denominators), or conditional (knowing when and why to apply the other two types of knowledge; for example, when taking a standardized multiple choice test, keep track of time, be strategic, and don't get bogged down on hard problems).

The intake and representation of information is called encoding. It is sent to the short term or working memory, acted upon, and those pieces determined as important are sent to long term memory storage, where they must be retrieved and sent back to the working or short-term memory for use. Short term memory has very limited capacity, so it must be kept active to be retained. Long term memory is organized in structures, called schemas, scripts, or propositional or hierarchical networks. Something learned can be retrieved by relating it to other aspects, procedures, or episodes. There are many strategies that can help in both getting information into long term memory and retrieving it from memory. The teacher's job is to help students to develop strategies for thinking and remembering.

Behaviorism

Behaviorist theorists believe that behavior is shaped deliberately by forces in the environment and that the type of person and actions desired can be the product of design. In other words, behavior is determined by others, rather than by our own free will. By carefully shaping desirable behavior, morality and information is learned. Learners will acquire and remember responses that lead to satisfying aftereffects. Repetition of a meaningful connection results in learning. If the student is ready for the connection, learning is enhanced; if not, learning is inhibited. Motivation to learn is the satisfying aftereffect, or reinforcement.

Behaviorism is linked with empiricism, which stresses scientific information and observation, rather than subjective or metaphysical realities. Behaviorists search for laws that govern human behavior, like scientists who look for pattern sin empirical events. Change in behavior must be observable; internal thought processes are not considered.

Ivan Pavlov's research on using the reinforcement of a bell sound when food was presented to a dog and finding the sound alone would make a dog salivate after several presentations of the conditioned stimulus, was the beginning of behaviorist approaches. Learning occurs as a result of responses to stimuli in the environment that are reinforced by adults and others, as well as from feedback from actions on objects. The teacher can help students learn by conditioning them through identifying the desired behaviors in measurable, observable terms, recording these behaviors and their frequencies, identifying appropriate reinforcers for each desired behavior, and providing the reinforcer as soon as the student displays the behavior. For example, if children are supposed to raise hands to get called on, we might reinforce a child who raises his hand by using praise, 'Thank you for raising your hand.' Other influential behaviorists include B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) and James B. Watson (1878-1958).

Cognitivism/Constructivism

Cognitivists or Constructivists believe that the learner actively constructs his or her own understandings of reality through interaction with objects, events, and people in the environment, and reflecting on these interactions. Early perceptual psychologists (Gestalt psychology) focused on the making of wholes from bits and pieces of objects and events in the world, believing that meaning was the construction in the brain of patterns from these pieces.

For learning to occur, an event, object, or experience must conflict with what the learner already knows. Therefore, the learner's previous experiences determine what can be learned. Motivation to learn is experiencing conflict with what one knows, which causes an imbalance, which triggers a quest to restore the equilibrium. Piaget described intelligent behavior as adaptation. The learner organizes his or her understanding in organized structures. At the simplest level, these are called schemes. When something new is presented, the learner must modify these structures in order to deal with the new information. This process, called equilibration, is the balancing between what is assimilated (the new) and accommodation, the change in structure. The child goes through four distinct stages or levels in his or her understandings of the world.

Some constructivists (particularly Vygotsky) emphasize the shared, social construction of knowledge, believing that the particular social and cultural context and the interactions of novices with more expert thinkers (usually adult) facilitate or scaffold the learning process. The teacher mediates between the new material to be learned and the learner's level of readiness, supporting the child's growth through his or her 'zone of proximal development.'

Humanism

The roots of humanism are found in the thinking of Erasmus (1466-1536), who attacked the religious teaching and thought prevalent in his time to focus on free inquiry and rediscovery of the classical roots from Greece and Rome. Erasmus believed in the essential goodness of children, that humans have free will, moral conscience, the ability to reason, aesthetic sensibility, and religious instinct. He advocated that the young should be treated kindly and that learning should not be forced or rushed, as it proceeds in stages. Humanism was developed as an educational philosophy by Rousseau (1712-1778) and Pestalozzi, who emphasized nature and the basic goodness of humans, understanding through the senses, and education as a gradual and unhurried process in which the development of human character follows the unfolding of nature. Humanists believe that the learner should be in control of his or her own destiny. Since the learner should become a fully autonomous person, personal freedom, choice, and responsibility are the focus. The learner is self-motivated to achieve towards the highest level possible. Motivation to learn is intrinsic in humanism.

Recent applications of humanist philosophy focus on the social and emotional well-being of the child, as well as the cognitive. Development of a healthy self-concept, awareness of the psychological needs, helping students to strive to be all that they can are important concepts, espoused in theories of Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Alfred Adler that are found in classrooms today. Teachers emphasize freedom from threat, emotional well-being, learning processes, and self-fulfillment.

*Some theorists call Rousseau's philosophy naturalism and consider this to be a world or metaphysical level philosophy (e.g. Gutek)

Think about It:Educational Philosophies Quotes

- Which psychological orientations are most compatible with which educational philosophies? Explain.

- Explain the differences in focus of the educational philosophies and psychological orientations. Are there also similarities?

- Non-western philosophies have also influenced American education, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Native American and African American philosophies. Find out about these and think about their current influences in education and where they might possibly be of value.

This is the second in a new series of blog postings by the Anthropology Teaching Forum (ATF) at the University of Texas, San Antonio. The first post introduced the ATF and its goal of building a strong teaching culture to match the research focus of the graduate program. This post offers a recap of a recent discussion on teaching philosophies—what they are, how they are defined, and how they inform different teaching styles—hosted by the ATF.

Teaching philosophies are ways to explore one’s own perspective on teaching and to communicate that perspective to students, hiring committees, and other educators. We discussed how to explore learning philosophies and general philosophical perspectives as personal context of your unique teaching philosophy.

One key introductory note is necessary before diving into the meat of our discussion. Over the course of our meeting, we found that a realistic distinction should be made between teaching philosophy as our main topic and teaching statements that make their way into job packets sent to hiring committees. The discussion here is most relevant to (idealistic, perhaps) teaching philosophy recognition and development. However faithful teaching statements are to teaching philosophies depends on the nature of the job, your teaching experience, and (rather cynically) your job desperation level. We acknowledge that teaching philosophies may be altered or padded to suit specific hiring opportunities but the focus here is on the teaching philosophy you carry around in your head more than anything you draft for a specific audience.

Leah discussed three key resources: Neil Haave (2014) on reflecting about your teaching philosophy, Maryellen Weimer (2014) on learning philosophies, and J.E. Beatty and colleagues (2009) on how general philosophy underpins teaching philosophies. Leah described Haave’s (2014) and Weimer’s (2014) emphasis on recognizing your learning philosophy as the foundation for your teaching philosophy. Learning philosophies are distinct from learning style (auditory, visual, etc.) and focus rather on motivations behind learning and the value you place on learning. Leah particularly emphasized a key facet of learning philosophies that struck her: how one deals with difficult learning experiences and those times when one may fail at understanding or mastering specific content. How does this affect how we approach learning? Further, how does this affect how we approach teaching? Leah discussed how she sees this particularly tied to a message in Haave (2014): instructor awareness and remembrance of what it is like to learn something brand new for the first time without the context developed over years of academic training and research. Leah suggested that this awareness of the students’ position (particularly in introductory courses) can and should relate to how instructors engage with student learning philosophies.

One point lacking in the discussion of exploring learning philosophy with teaching philosophy is the awareness of how instructor learning philosophies may mesh and/or oppose students’ learning philosophies. We discussed how direct experience with students and even institutional demographics (as a gauge before direct experience) may guide your understanding of student learning philosophies. It is important to stress that while the instructor’s awareness of their own learning philosophy is important as they engage in developing and/or revising their teaching philosophy, it is as important to be aware of student learning philosophies and the ways in which instructors and students compare/differ in how they are motivated to learn. One way that you can use learning philosophy to develop teaching philosophy is presented as a series of six interrelated questions in Haave (2014) to recognize exemplary personal learning and teaching experiences, how they connect, and how to provide such exemplary experiences for students.

One sub-topic in our discussion of teaching philosophies is the distinction of pedagogy and andragogy. Most of us are very familiar with the term pedagogy, referring to the methods and practice of teaching generally. If we were to do a search of teaching philosophy statements cross-disciplinarily, pedagogy might be top of the list of most frequently used terms. If taken literally and historically, pedagogy etymologically refers to teaching (or leading) children while andragogy refers to teaching (or leading) adults (Holmes and Abington-Cooper 2000). The age based distinction of child and adult while relevant for primary or secondary education, may not be the most relevant approach for a higher learning context. It may be more effective to think about the distinction of general novices (e.g. children) and general experienced (e.g. adults who are not novices in terms of life experience but may be novices in terms of course content).

In terms of how this may affect your teaching philosophy, it is interesting to reflect on how you perceive your students. Do you see the students who populate your classroom as general novices that need controlled and dictated leadership? Do you see your students as experienced, with skills that make them equipped to develop the specific knowledge base relevant to your class via their own constructions and ownership? We discussed how this dichotomy is useful and how it is overly simple. We recognized the need for a blended approach, specifically in courses with heavy factual content loads, such as biological anthropology (i.e. fossil record and human evolutionary trends). Overall, the recognition of how you as an instructor view your students is important for developing a relevant and authentic teaching philosophy.

Major Educational Philosophies

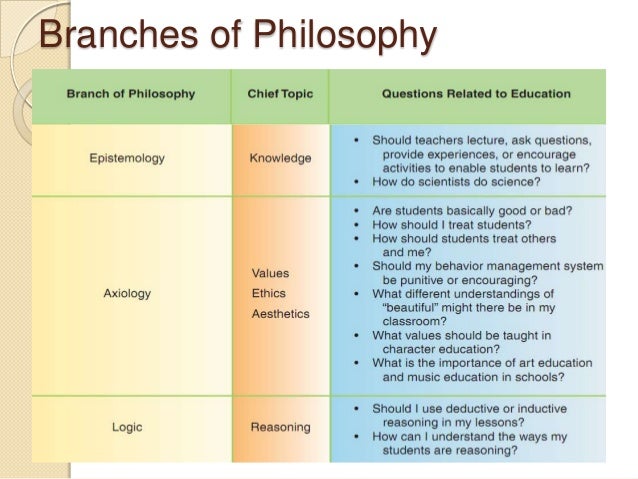

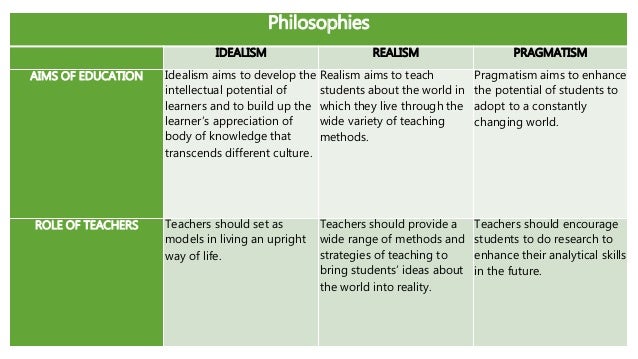

The bulk of our discussion centered on Beatty and colleagues’ (2009) novel approach to contextualizing teaching philosophies. The authors suggest grounding teaching philosophies in general philosophical perspectives. They describe five general philosophical perspectives (idealism, realism, pragmatism, existentialism, and critical theory) via three criteria: metaphysics (what is real?), epistemology (how do I know what I know?), and axiology (what is the basis of my judgment and ethics?). The chart (Beatty et al 2009: 107) below summaries these perspectives well:

Beatty et al (2009) describe how each general philosophical perspective may impact teaching philosophy. We discussed where we personally see ourselves falling in this classification and how these personal perspectives affect how we teach. For example, Leah confessed her general alignment with the existentialist emphasis on subjectivity and the importance of personal choice. This is reflected in her clear focus on student choice in the classroom via focused archaeological research projects, seminar assessment, and choice-driven activities such as mock excavations. Beatty et al (2009: 109) state that instructors with an existentialist perspective are more likely to emphasize experiential learning in their classrooms. It is not difficult to trace Leah’s keen devotion to experiential learning through previous posts and recaps for the ATF! Dr. Mary Kelaita (Post-Doctoral Fellow in the UTSA Department of Anthropology) described her personal connection to relating unknowns (course content) to knowns (from personal experience) during her undergraduate career. Through awareness of her pragmatist perspective, she guides her students to make similar personal connections with content in biological anthropology courses. All participants acknowledged that while this classification is insightful, it does not follow that we are beholden to only one perspective. We can be a blend of two or several. The recognition and awareness of wherever we do fall is what can impact or improve your teaching philosophy.

We discussed the practicalities of what this philosophical approach to teaching philosophies means for how you present your teaching philosophy to others. Is it necessary to spend time in already savage page limits or word counts to expound on why you lean existentialist or towards critical theory? Probably not. But reflecting on these philosophical perspectives can be significant to contextualizing your unique philosophy of teaching and why you are motivated to teach the way you do. Teaching statements can reflect these general perspectives and provide insight into you as an individual.

To conclude the meeting, Leah emphasized the PROCESS of reflection for teaching philosophies. While the practicalities of writing teaching statements are important, formalizing your teaching philosophy for yourself and thinking about how, ideally, you want to teach can be an opportunity to directly improve and connect back to the classroom. Particularly, Leah emphasized reflection on how your teaching philosophy (inclusive of your learning philosophy and general philosophical perspective) relates to/engages with/ignores your students’ learning philosophies. It may be a good exercise to recognize learning philosophies evident among your students and how your teaching philosophy plays to their strengths, challenges them to try new things, or flies straight over them. Further, we recognized that students being exposed to a diversity of teaching philosophies (via different professors, disciplines, and year levels) is likely a very good thing for the development of critical thinkers and general life skills.

All participants expressed interest in this topic and these novel ways of attacking teaching philosophies. In the future, ATF hopes to organize an update or extension to this session to directly discuss the construction and finagling of teaching statements.

Leah McCurdy can be reached directly at leah.mccurdy@mavs.uta.edu.

References:

Beatty, J.E., J.S.A. Leigh, and K.L. Dean. 2009. Philosophy Rediscovered: Exploring the Connections Between Teaching Philosophies, Educational Philosophies, and Philosophy. Journal of Management Education 33(1): 99-114. http://jme.sagepub.com/content/33/1/99.abstract

Haave, Neil. 2014. Six Questions That Will Bring Your Teaching Philosophy into Focus. Faculty Focushttp://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/philosophy-of-teaching/six-questions-will-bring-teaching-philosophy-focus/

Holmes, Geraldine and Michele Abington-Cooper. 2000. Pedagogy vs. Andragogy: A False Dichotomy? The Journal of Technology Studies 26 (2). http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JOTS/Summer-Fall-2000/holmes.html

Weimer, Maryellen. 2014. What’s Your Learning Philosophy? Faculty Focus

http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-professor-blog/whats-learning-philosophy/