Plots Exposition

Plot is the way an author creates and organizes a chain of events in a narrative. In short, plot is the foundation of a story. Some describe it as the 'what' of a text (whereas the characters are the 'who' and the theme is the 'why'). This is the basic plot definition. This is a power point describing the plot elements, such as exposition, rising action, etc. That uses short video clips to help describe each element.

When you’re writing a story, plot and structure are like gravity. You can work with them or you can fight against them, but either way they’re as real as a the keyboard at your fingertips.

Getting a solid grasp on the foundations of plot and structure, and learning to work in harmony with these principles will take your stories to the next level.

What is the best structure for a novel? How do you plot a novel?

Photo by Simon Cocks (Creative Commons). Adapted by The Write Practice.

Plot Exposition Example

Want to learn more about plot? Check out my new book The Write Structure which helps writers make their plot better and write books readers love. It’s only $2.99 for a limited time. Check out The Write Structure here.

Definition of Plot and Structure

What is story plot? What is the best structure for a novel?

Plot is the series of events that make up your story, including the order in which they occur and how they relate to each other.

Structure (also known as narrative structure), is the overall design or layout of your story.

While plot is specific to your story and the particular events that make up that story, structure is more abstract, and deals with the mechanics of the story—how the chapters/scenes are broken up, what is the conflict, what is the climax, what is the resolution, etc.

You can think of plot and structure like the DNA of your story. Every story takes on a plot, and every piece of writing has a structure. Where plot is (perhaps) unique to your story, you can use an understanding of common structures and devices to develop better stories and hone your craft.

Essential Narrative Devices for Plot and Structure

Here are three common devices essential to fiction—but especially important in writing novels—that will help frame any current story you’re working on, and give you a jumping off point to learn more about plot and structure.

Three Act Structure

This idea goes back to ancient Greek dramatic structure theory, so you know it’s been time-tested. Aristotle said that every story has a beginning, a middle, and an end (in ancient Greek, the protasis, epitasis, and catastrophe), and ancient Greek plays often follow this formula strictly by having three acts.

Still commonly used in screenwriting and novels today, the three act structure is as basic as you can get: every story ever written has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Narrative Arc

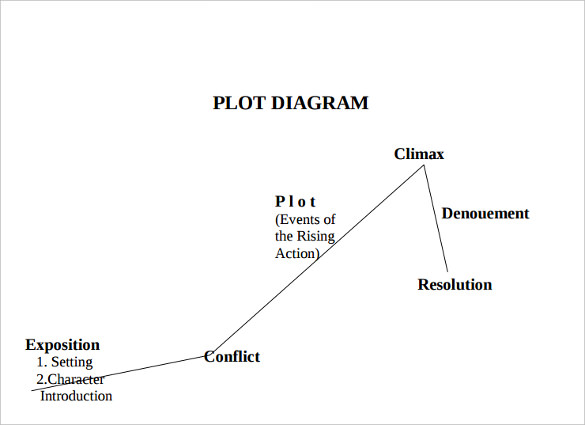

Also called Freytag’s pyramid, the narrative arc is made up of the following pieces:

- Exposition — The opening of the story, including a reader’s introduction to characters and settings.

- Rising Action — A series of events that complicates matters for your characters, and results in increased drama or suspense.

- Climax — The big showdown where your characters encounter their opposition, and either win or lose.

- Falling Action — A series of events that unfold after the climax and lead to the end of the story.

- Resolution — The end of the story, in which the problems are resolved (or not resolved, depending on the story.) Also called the denouement, catastrophe, or revelation.

For more on this, check out our thorough Freytag’s Pyramid guide here.

Again, this is an abstract device used to describe the narrative arc of all stories, which is why it’s so powerful and commonly used in dramatic structural theory.

Ask yourself how your story fits into this framework. If it doesn’t, what’s missing?

How to Introduce Plot to Your Story: A Disturbance and Two Doorways

I originally found this concept in Plot & Structure by James Scott Bell.

The disturbance is whatever happens early on in your story that upsets the status quo. It can be a strange phone call in the middle of the night, news of the death of a close relative, or anything that is a threat or a challenge to your protagonist’s ordinary way of life.

But a disturbance isn’t enough. Something has to propel your protagonist from the beginning into the middle of the story, and from the middle to the end. Bell suggests:

“How you get from beginning to middle (Act I to Act II), and middle to end (Act II to Act III), is a matter of transitioning. Rather than calling these plot points, I find it helpful to think of these two transitions as ‘doorways of no return.’”

Every story has a disturbance and two doorways of no return. You can learn more about this concept, as well as a whole host of other indispensable devices, by reading Bell’s book.

For more on how to create drama within each scene of your story, check out our guide on literary crisis.

Plot Exposition Worksheets

Take Your Novel’s Plot and Structure to the Next Level

An understanding of story plot and story structure are essential to the creative writer’s understanding of craft. If you can master them, you can use them as a foundation for your work. Mix a good plot with solid structure, pour in your characters, toss in a dash of setting, and you’re most of the way to a fully cooked story.

How about you? What tips do you have for writing plots? How do you structure your novel? Share in the comments section.

Need more plot help? After you work on practicing this structure in the exercise section below, check out my new book The Write Structure which helps writers make their plot better and write books readers love. Low price for a limited time!

PRACTICE

For today’s practice, you have five different options. That’s right, FIVE! Here they are:

- Identify the narrative arc of your story. Where does the rising action start? What is the climax? What is the falling action? Do you already know the resolution, or is that something you have yet to work out?

- Divide your story into three acts (even if you don’t divide the story into acts in the final product.) Where does each act end and the next begin?

- Write down what the disturbance is in your story. Identify the two doorways of no return. What is the propellant that pulls your protagonist through the first doorway? Through the second?

- Outline a new story following the three act structure. Look at it from a 50,000 foot view. What can you improve?

- Outline a new story by starting with the disturbance and two doorways. Think about what pulls your character through each doorway. Remember, a disturbance isn’t enough!

After you finish your practice, share what you learned in the comments section.

Happy writing!

Narrative exposition is the insertion of background information within a story or narrative. This information can be about the setting, characters' backstories, prior plot events, historical context, etc.[1] In literature, exposition appears in the form of expository writing embedded within the narrative. Exposition is one of four rhetorical modes (also known as modes of discourse), along with description, argumentation, and narration, as elucidated by Alexander Bain and John Genung.[2]

In essays[edit]

An expository paragraph presents facts, gives directions, defines terms, and so on. It should clearly inform readers about a specific subject.[3]

An expository essay is one whose chief aim is to present information or to explain something. To expound is to set forth in detail, so a reader will learn some facts about a given subject. However, no essay is merely a set of facts. Behind all the details lies an attitude, a point of view. In exposition, as in other rhetorical modes, details must be selected and ordered according to the writer's sense of their importance and interest. Although the expository writer isn't primarily taking a stand on an issue, he can't—and shouldn't try to—keep his opinions completely hidden.[4]

In fiction[edit]

An information dump (or 'infodump') is a large drop of information by the author to provide background he or she deems necessary to continue the plot. This is ill-advised in narrative and is even worse when used in dialogue. There are cases where an information dump can work but in many instances, it slows down the plot or breaks immersion for the readers. Exposition works best when the author provides only the surface—the bare minimum, and allows the readers to discover as they go.[5]

Indirect exposition/incluing[edit]

Indirect exposition, sometimes called incluing, is a technique of worldbuilding in which the reader is gradually exposed to background information about the world in which a story is set. The idea is to clue the readers in to the world the author is building without them being aware of it. This can be done in a number of ways: through dialogues, flashbacks, characters' thoughts,[6] background details, in-universe media,[7] or the narrator telling a backstory.[6] Instead of saying 'I am a woman', a first person narrator can say 'I kept the papers inside my purse.' The reader (in most English-speaking cultures) now knows the character is probably female.[8]

Indirect exposition has always occurred in storytelling incidentally, but is first clearly identified, in the modern literary world, in the writing of Rudyard Kipling. In his stories set in India like The Jungle Book, Kipling was faced with the problem of Western readers not knowing the culture and environment of that land, so he gradually developed the technique of explaining through example. But this was relatively subtle, compared to Kipling's science fiction stories, where he used the technique much more obviously and necessarily, to explain an entirely fantastic world unknown to any reader, in his Aerial Board of Control universe.[9]

Kipling's writing influenced other science fiction writers, most notably the 'Dean of Science Fiction', Robert Heinlein, who became known for his advanced rhetorical and storytelling techniques, including indirect exposition.

The word incluing is attributed to fantasy and science fiction author Jo Walton.[10] She defined it as 'the process of scattering information seamlessly through the text, as opposed to stopping the story to impart the information.'[11] 'Information dump' (or info-dump) is the term given for overt exposition, which writers want to avoid.[12][13] In an idiot lecture, characters tell each other information that needs to be explained for the purpose of the audience, but of which the characters in-universe would already be aware.[14] Writers are advised to avoid writing dialogues beginning with 'As you well know, Professor, a prime number is...'[15][16][17]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Kaplan SAT Subject Test: Literature 2009–2010 Edition. Kaplan Publishing. 2009. p. 60. ISBN978-1-4195-5261-8.

- ^Smith, Carlota S. (2003). Modes of Discourse: The Local Structure of Texts. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN978-0-521-78169-5. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^Sebranek et al. (2006, p. 97)

- ^Crews (1977, pp. 14–15)

- ^Bell (2004, p. 71) harvtxt error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBell2004 (help)

- ^ abDibell, Ansen (1988). Plot. Cincinnati, OH: Writer’s Digest Books. ISBN0-89879-303-3. *Kernen, Robert (1999). Building Better Plots. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest Books. p. 51. ISBN0-89879-903-1.

- ^Morrell, Jessica Page (2006). Between the Lines: Master the Subtle Elements of Fiction Writing. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer's Digest Books. p. 64. ISBN978-1-58297-393-7.

- ^The Writer's Writing Guide: Exposition

- ^Rudyard Kipling Invented SF

- ^Michelle Bottorff (11 June 2008). 'rec.arts.sf.composition Frequently Asked Questions'. Lshelby.com. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^'papersky: Thud: Half a Crown & Incluing'. Papersky.livejournal.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^Bell, James Scott (22 September 2004). Write Great Fiction – Plot & Structure. Writer's Digest Books. p. 78. ISBN978-1-58297-684-6.

- ^=http://www.screenplayology.com/content-sections/screenplay-form-content/3-3/

- ^John Ashmead; Darrell Schweitzer; George H. Scithers (1982). Constructing scientifiction & fantasy. TSR Hobbies. p. 24. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^Kempton (2004). Write Great Fiction – Dialogue. F+W Media. p. 190. ISBN1-58297-289-3.

- ^Rogow (1991). FutureSpeak: a fan's guide to the language of science fiction. Paragon House. p. 160. ISBN1-55778-347-0.

- ^'Info-Dumping'. Fiction Writer's Mentor. Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

References[edit]

- Bell, James Scott (2004), Write Great Fiction: Plot & Structure, Cincinnati: Writer's Digest Books, ISBN1-58297-294-X

- Crews, Frederick (1977), The Random House Handbook (2nd ed.), New York: Random House, ISBN0-394-31211-2

- Sebranek, Patrick; Kemper, Dave; Meyer, Verne (2006), Writers Inc.: A Student Handbook for Writing and Learning, Wilmington: Houghton Mifflin Company, ISBN978-0-669-52994-4